It’s now been over six months since students last had face-to-face classes for more than two consecutive weeks, and the future of this new year is still uncertain. Behind their screens in their parents’ homes for the lucky ones, or in their 9 m2 homes for some, they are trying to keep up with their online courses. As Nathan Tedga, president of a student association in Mulhouse, puts it in an open letter to the President of the Republic, they are among “the last confined”. The impact of the health crisis on students’ mental health is significant, and requires our full attention.

Why open the shops without opening the universities? Why can high-school, HND and preparatory classes have lessons in class, when there are just as many of them as academics in the lecture theatres ? Students feel so disregarded that a trend called ghoststudents appeared on Twitter last week, lamenting the lack of action in the face of a situation that is becoming more and more frequent.

Students in digital divide and psychological distress

In addition to a sense of injustice, students are faced with isolation. Disconnected from reality and campus life, it’s hard to stay focused and motivated. When first confined, eight out of 10 students were already afraid of dropping out of school. For 40.5% of the students surveyed by Article 1*, it’s the contact and exchange with professors during physical classes that they miss the most.

Extracurricular life is also essential to their success. For Rose, a final-year law student, it’s hard to keep her spirits up, and she misses the moments of life that used to give her a breather:

“When I stay at home and bad news arrives, I can’t escape it. Beyond the fact that my classes aren’t necessarily motivating, not being able to take my mind off things with my friends makes it even harder.”

Add to this the financial worries of students. According to an Insee report from early 2020, 1 in 4 students work during their studies, to support themselves. Most of these students lost their jobs during the health crisis. 45% of young people surveyed by Article 1* in November 2020 are concerned about their situation. Student precariousness is not new, and was already on the rise before the confinement caused by rising rents and material costs. The digital transition, which comes at a cost to students, creates a new gap in access to higher education. This is what we call the digital divide.

The term “digital divide” refers to unequal access to digital tools, a gap widened by higher material costs. Going remote means having a computer, a good Internet connection, and wherever possible, an environment that facilitates work. These conditions are not readily available, and according to the study we carried out after the first lock-in, 2% of students are still affected. In November, nearly three quarters of the 700 young people questioned by Article 1, an association fighting for equal opportunities, were stressed and exhausted by the uncertainty of the crisis.

* association fighting for equal opportunities

What solutions are in place ?

Universities are implementing solutions to reduce this divide, by making computers and 4G keys available to students who don’t have access to them. Our study revealed that during the first lockdown, over 4,800 computers were made available to students, and over 1,000 were donated. These are fine initiatives, financed for the most part by the universities, and which for the second lockdown were supported by certain regions.

Universities are organizing a return to the classroom in small groups, with priority given to students considered to be the most fragile and most affected by the crisis. While this is very useful, and gives students a glimpse of movement in the measures taken by the government, students are at their wits’ end, and are rightly calling for greater consideration.

Are students increasingly facing psychological distress ?

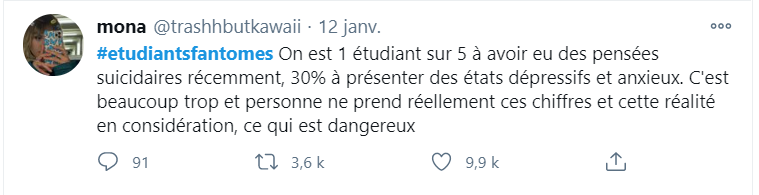

Student life before Covid was already a source of stress. 15% of them, according to criteria derived from international classifications, suffer from a depressive episode compared with 11% in the total French population in 2018*. These figures are reported to be on the rise since confinement, despite the difficulty of measuring them. Indeed, the notion of mental health is often ill-defined and its indicators vary from study to study, as The Conversation article explains.

“We don’t yet have figures on the suicide rate among students since the start of confinement. Anticipating them from observations is therefore complicated. However, we do know from the statistics of the Student Life Observatory that suicidal urges have doubled, and that depressive states have multiplied by 2.5″, Dr Dominique Monchablon, psychiatrist and head of department at the Relais student in Paris.

Health centers offer psychological care. However, they are not able to accommodate all students : “Even so, there is an under-supply of care for students. Many psychologists and psychiatrists specialize in children and adults. But there are few who specialize in students or young adults”, points out Dr Dominique Monchablon.

Universities are not slackening their efforts and are taking the situation of students into consideration. This has led to some excellent initiatives, such as the New Year’s Eve events organized by the University of Lille. Students, professors and even psychiatrists offer help on social networks, with advice, listening and free consultations. Recently, the University of Rouen organized a giveaway on the Mont Saint-Aignan campus.

“I’m in favor of reopening universities, subject to appropriate protocols.” – Valérie Pécresse, BFM TV, January 18, 2021

Valérie Pécresse announces the opening of a student emergency plan by the Ile de France region, in addition to the State’s measures. Firstly, 400 housing units will be made available for students in extremely precarious situations. A dedicated student mental health helpline, ecouteetudiants-iledefrance.fr, will enable students to contact one of 150 psychologists, assess their state of health and benefit from free consultations. The plan also includes funding for 10,000 computers and guaranteed access to student loans.

Students’ dual approach to distance learning

We hear a lot, and rightly so, about the plummeting mental health of students as a result of this brutal transition. What about those who prefer distance learning ? And yes, they do exist !

It’s interesting to note that some of the students are complacent in this situation. Indeed, when we interviewed them, we realized that some, like Amanda, prefer to study at home :

“Campuses and socializing with other students are a source of anxiety for me, and it exhausts me. I’ve found I’m much more comfortable and focused at home.”

This raises another issue, that of the anxiety-inducing climates that can be found on campus, and the state of students’ mental health prior to the crisis. As we pointed out earlier, 15% of students in 2018 claim to be in a state of depression.

Pressure to succeed at school, financial problems, doubts about the future – what if social pressure was also a factor? You all know that person who had a bad time at school, maybe it was even you, because you didn’t feel you fit in with the group of people you studied with. Because you couldn’t integrate an impersonal work method, a rhythm that didn’t suit you and didn’t give you the opportunity to explore other ways of organizing your time, ultimately reinforcing the idea that that time was wasted.

What if digital technology enabled everyone to choose their own learning methods ?

For Louise, in her final year of a Master’s degree, it’s also a way of focusing her learning and optimizing her time. Instead of being bored in class with notions she’s already understood, she can get on with other tasks : “I feel I’ve got some life time back, and can use this time, during which I was on Facebook, to manage other projects”. This duality shows, firstly, the impressive adaptability of some students, and secondly, that face-to-face learning is not for everyone. Let’s not forget that some students have additional activities (entrepreneurship, parental responsibilities) or simply have difficulty adapting to the course formats currently on offer (social anxiety, difficulty concentrating).

A new debate opens up following these rather unexpected answers. Do we have to join a group if we don’t feel the need to ? Wouldn’t the development of flexible learning paths be the answer to the problem of incomplete student integration ? Should we apply the same pedagogy to heterogeneous profiles ? In short, for us, digital technology is an opportunity to personalize our courses, to make them more flexible and tailored to our needs.

Educational hybridization: we are convinced that digital and face-to-face learning are complementary concepts.

Digital technology, as a complement to face-to-face teaching, creates an enormous field of possibility and adaptability. Using the new tools effectively means being able to put in place solutions that are adapted to students, getting them to work at different levels, depending on their mastery of the subject. Digital technology can also make it possible to take into account all student profiles, and not just some of them.

Creating flexibility means allowing everyone to take their courses as they wish. Being a student should be an opportunity to learn, to develop and to move serenely towards the future, and this requires adaptability and the ability to choose.

Wouldn’t trusting students, listening to them and taking into account the way they work be the best way to offer them appropriate solutions?

What if they, who have grown up with digital technology, could teach us and guide us in this transformation of pedagogy?