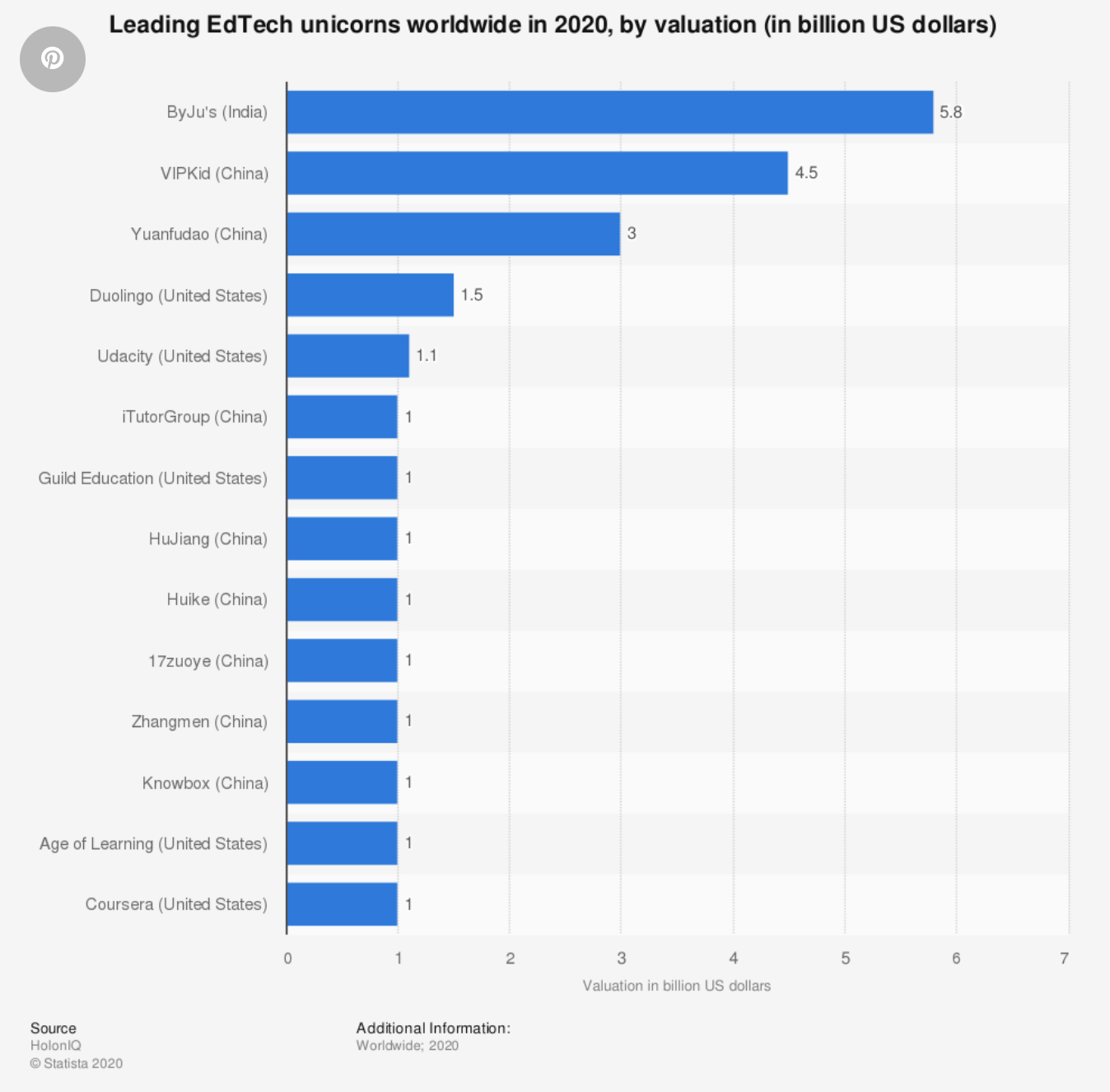

Like all the world’s EdTech markets, India’s has seen a great acceleration during the pandemic. Numerous startup are appearing, and those already at the forefront, such as Byju’s, the world’s most valuable EdTech, continue to grow. This explosion has happened for a number of reasons, but it could see a fall as stunning as the Chinese market, which we studied in one of our previous #EdTechWeekBySimone. We explain!

Why is there such a buzz around EdTech in India? What are the country’s challenges and is there a risk of a market downturn? 🇮🇳

The Indian edtech market is one of the largest in the world, mainly due to its population density. India is the world’s second most populous country. Of its large population (1.3 billion in 2019), 50% are under the age of 25, and 28% are under the age of 14 – a great development opportunity for new educational technologies. Investors have understood this, and are increasing their investments from 0.5 to 4 billion between 2019 and 2021! Dozens of start-ups are jumping on the bandwagon, advocating “more fun education”. Millions of learners are now using these “education-transforming technologies”, and they’re also being exported abroad, like the interactive Quizizz platform that Anne-Emmanuelle Legrix-Pagès already told you about in a #Univ4Good episode !

Let’s take Byju’s as an example of this acceleration :

Byju’s, the learning application, is a solution that offers tutoring for K12 students and preparation for national and international exams.

Valued at $18 billion, it is one of the world’s leading EdTech companies. It claims 32 million users in 2019. Its expansion is also due to its numerous acquisitions, such as that of Aakash, one of the world’s largest coaching institutes for higher education students. It has spent over $2 billion on acquisitions in recent months. Today, it is preparing to raise over $150 million from the UBS group. To give you an idea, this sum represents the total capital invested in European EdTech in 2020.

Many Indian EdTechs use this fund-raising strategy. It enables them to move faster, and to surround themselves with experts to develop their start-ups nationally, but above all internationally.

But in the long run, what does it look like? 🤔

Today, the question is the country’s economic situation and the long-term consequences of this EdTech bubble.

The country is experiencing an economic rebound. After a sharp fall in purchasing power last year, India is now catching its breath and achieving record GDP growth (+23.3%) in Q2 2021, driven by manufacturing and construction. This is enabling people to invest more in education.

However, the country still faces a number of structural weaknesses, such as chronic poverty and unequal access to education. Of the estimated 270 million young people, 27% have no access to education or employment. For the middle class, the price of access to new technologies can represent significant sums, and the digital divide is widening. Some EdTechs are complaining about customer infidelity, linked to costs that are too high.

Nevertheless, the race to graduate is on, and following the example of China, parents are investing as much as possible in their children’s success. They don’t hesitate to go into debt, and even to move to the big cities to ensure their children have a future and pass the selective stage of higher education. Today, there are over 35 million students in higher education. Once on the job market, they face a new challenge: the employability crisis. The massive evolution of teaching methods and digital learning solutions has created a gap between the expectations of young people and the reality of the marketplace.

Will India suffer the same fate as China?

During 2021, the Chinese EdTech market faced strict restrictions on its activity. The evolution of EdTech was widening inequalities between students, and creating additional pressure on children whose parents were enrolling them en masse in online courses in the evenings, at weekends and during school vacations. The government then decided to curb this craze by banning evening and weekend courses, as well as by transforming K12 EdTech into a non-profit association. These decisions have had a major impact on the Chinese market.

While these restrictions could help the development of Indian EdTechs, won’t the country face the same problems?

The EdTech crisis in China may have a positive impact on the Indian market. As both countries rely on fund-raising, the loss of value in Chinese EdTechs may well direct investment to India.

Yet the country could find itself in the same crisis situation, a victim of too great a gap between the growth of this market and the reality of the country. But unlike China, the relationship with education is not the same. In China, families aim for excellence, even if it means exhausting their children under the constraints of learning. By adopting these restrictions, the government has curbed a new fad, dangerous for the mental health of China’s youth. In India, even if trends are changing, the major problem remains inaccessibility to education and employment. For many, the priority is to be able to feed themselves, even if this means sending their children out to work at an early age.

Government decisions are not made in the same way. In the world’s largest democratic country, market decisions are made by many hands, and the country is agreed on the importance of education.

Finally, in Indian education, tutoring is a common practice. It is still carried out physically in dedicated centers, but withdrawing access to online tutoring resources would run counter to the objective of equality and the right to practice or trade guaranteed by the Indian government.

In order to reap the benefits of this EdTech bubble, India must succeed in reducing inequalities in access to education, by making more teaching resources available, and also succeed in keeping up with graduate students, who are entering a job market that is still not very attractive! These are difficult challenges, to which digital technology, if mastered, can provide a partial response.